A new opportunity for landowners and developers? Carter Jonas considers conservation covenants

The agricultural community is preparing for the biggest shake-up to face the sector in 40 years.

The agricultural community is preparing for the biggest shake-up to face the sector in 40 years. The long-awaited Agriculture Bill has been brought before parliament, as well as the Environment Bill that sets out how the government will build on the 25 Year Environment Plan.

Farmers will now be paid subsidies based on their care of the environment, a shift announced previously as the UK leaves the EU and its agricultural policy.

Against this backdrop, many in the industry are looking for alternative ways in which they can support their business. The Environment Bill could provide opportunities around natural capital and environmental standards. One aspect of the Bill is the proposed introduction of legislation for conservation covenants. These are private and voluntary agreements between a landowner and a responsible body, such as a conservation charity, allowing for positive or restrictive obligations to fulfil a conservation objective.

These covenants are attached to the land itself so, should the land change hands, the covenant continues to bind future landowners. The intention is for the parties to be free to negotiate terms to suit their specific circumstances and requirements, including the length of time that the agreement applies.

Currently, the only parties permitted to enforce covenants are the adjacent landowner, or landowners, and the National Trust, but there are proposals for this to be amended and the remit extended to charities and possibly registered for-profit bodies.

The benefit of using such covenants are threefold. It will provide a long-term and robust mechanism for ensuring biodiversity net gain during development, a requirement under the National Planning Policy Framework. It is expected that developers would be able to deploy such a covenant as a means of facilitating development by securing compensatory habitat creation elsewhere.

The use of a conservation covenant could help enable a developer to facilitate the required environmental improvements to natural capital; the landowner would be paid to implement a change on their land, to leave the environment in a measurably better state, whilst a responsible body would be paid to accept, monitor and enforce the covenant.

In this case, the covenant would stipulate future land use protocols or management systems and the land would not need to be owned by the responsible body.

This would be one way for a developer to secure the required biodiversity net gain, and landowners may find that another route would allow them more flexibility in terms and duration.

Secondly, an alternative and more philanthropic use might see such covenants being created by existing landowners or benefactors looking to create lasting legacies. A conservation covenant could be devised to secure an environmental benefit to natural capital that accords with their own beliefs and objectives, such as enduring organic status or the creation of habitats to encourage biological diversity. As the land is passed through generations or bought and sold, the limitations on the way the land is used and employed will remain.

Finally, it is also possible that corporate polluting organisations could seek to achieve their environmental objectives and off-set their carbon or other emissions by entering these covenants.

The concept is not without its drawbacks. Concerns have been raised regarding the ongoing funding and maintenance required to comply with covenants in the future, and who should be responsible. Landowners will need to consider the long-term impact of such covenants whilst responsible bodies will have to ensure that they have the management skills and resources to oversee and enforce them. Those considering offering biodiversity offsetting should also look carefully into whether the short-term increase in income is enough to counterbalance any loss of potential value moving forward.

The requirement to offset biodiversity losses is likely to become a routine requirement when a habitat or natural resource is adversely impacted by development. Carter Jonas, with a rural team who manages over a million acres of land throughout the UK, and a planning and development team advising on 23,000 acres of development land, is well-placed to provide proactive advice to enable developers and landowners to work together to mutual benefit.

If you would like to discuss this subject or any of your property requirements, please contact Carter Jonas.

More in Commercial Property

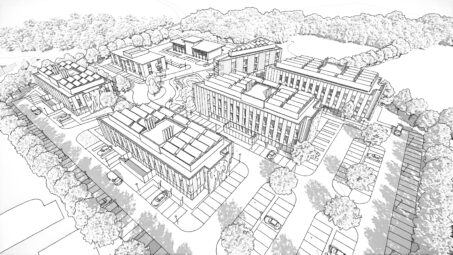

Wootton Science Park unveils £35 million masterplan for new SME science...

Hartwell Plc, the automotive and property development company, has unveiled emerging designs to deliver new carbon efficient lab and workspace buildings for small and medium sized science and technology companies and amenities at Wootton Science Park to the south-west of Oxford.

Green light for Bicester Motion’s new £50 million Innovation Quarter to...

Detailed designs for seven new, prestigious HQ buildings which total 212,030 sq ft (19,698 sq m) and will be built at Bicester Motion’s new Innovation Quarter have been given the green light by Cherwell District Council.

Oxford Innovation Space to manage £14m Vulcan Works Creative Hub

The high-end workspaces are expected to be available from early next year.

From this author

UK Biomass Potential for BECCS Land Occupier Survey

Carter Jonas have been commissioned to provide research and information on the future of Biomass and the potential supply of feedstock for power generation within the UK.

Are we overcoming the polarisation and prejudice that later living schemes...

In a 2018 article, we highlighted that communities are too often unbalanced and polarised and warned, ‘If age segregation is defining our communities today, then action must be taken to prevent it escalating further’. Three years on, Planning & Development Insite considers whether society and our industry has actually made any progress.

Biodiversity, Amenity and Diversification

The tree drivers for land purchases you may not have considered.